In Russia, negli anni tra il 1947 e il 1964, era molto difficile potere ascoltare, folk underground, registrazioni di performers politici (come Lescheko o Vertinsky), jazz e naturalmente rock and roll di produzione straniera, generi e canzoni considerate potenziali minacce dal Cremlino anche in assenza di messaggi antisovietici.

La soluzione arrivò dall’Ungheria, dove i controlli della censura erano meno puntuali e oppressivi. La radio statale di Budapest realizzava infatti registrazioni professionali su lastre radiografiche, anche di glorie nazionali come Bela Bartok.

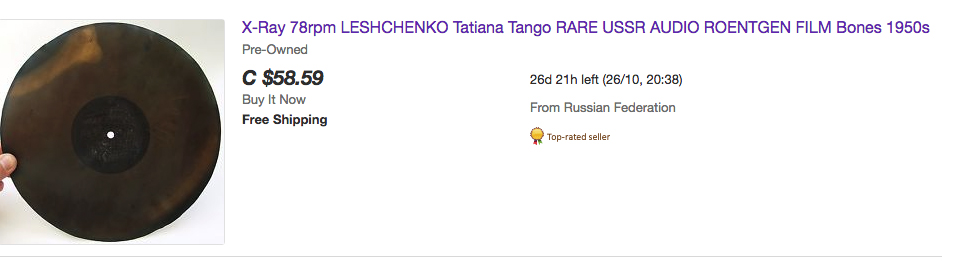

Ruslan Bogoslowskij e Boris Taigin iniziarono ad usare macchine costruite per copiare registrazioni militari su lastre radiografiche, facilmente reperibili presso gli ospedali (le lastre venivano poi ritagliate e bucate al centro) incidendo registrazioni musicali a 78 giri riproducibili da qualsiasi giradischi.

Su ognuno di questi dischi (incisi su di un solo lato e dapprima ricavati da lastre in nitrato o acetato, ricoperte da uno strato protettivo) spesso non apparivano titoli di canzoni né nomi di gruppi, soltanto un codice.

Nacquero così i preziosi Roentgenizdat: bootleg che costavano al massimo un rublo e mezzo, contro i cinque rubli di un normale disco, si consumavano in pochi mesi e possedevano una qualità audio misera.

Chi era colto in possesso di musica “ideologicamente straniera” rischiava la prigione e veniva immediatamente licenziato. Bogoslowskij stesso venne arrestato tre volte e nel 1958 la censura dichiarò ufficialmente illegali i roentgenizdat.

ll mercato si era però ingigantito e la musica occidentale si diffuse rapidamente in tutta l’Unione Sovietica; questi dischi si trovavano in tutte le case oltre ad essere usati anche nelle radio per diffondere musica “non illegale”.

La fine di questa era arriverà con l’avvento delle musicassette (magnitizdat), che garantivano una maggiore facilità di riproduzione, prospettiva di veicolare ormai punk e musiche con messaggi politici più espliciti ma paradossalmente minori rischi legali, dato che ad ogni sovietico era consentito il possesso di un registratore a nastro. Al contrario, i macchinari per la stampa su carta rimarranno sotto il controllo dello stato.

Nel 2016 Stephen Coates e Paul Heartfield hanno prodotto il documentario “X Ray audio bone music”, premiato come miglior documentario al Festival del Cinema russo a Londra e proiettato anche al Trieste Film Festival 2017.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XMCCYnDvpJQ

Questo il link del sito che riguarda l’ X -Ray audio Project

https://www.rbth.com/arts/2015/09/30/boogie_bones_underground_soviet_x-ray_lps_come_to_uk_49679.html

Il medium è il messaggio, insomma, mi chiedo infine se il primo disco dei Faust (pubblicato nel 1971) non fosse proprio un omaggio

ai roentgenizdat. E’ tutto, il prossimo blog sarà incentrato sul reportage (sonoro) di viaggio.

NOTE:

Q This record, if you notice, is made from an X-ray film. It was sent to me in the early 1960s form a pen pal. The X-ray was used as a raw material to make this record. It was smuggled out of the U.S.S.R. This was considered Jazz because it represented Western Imperialist “Bally hoo” as my pen pal called it. The song on the record is “Tweedle Dee Dee,” which was popular in the 1960s. It plays clearly on 78-RPM mode on a standard phonograph. How valuable do you think this item is and do you think it is saleable? — H.B., Brooklyn, N.Y.

A During the late 1930s and early 1940s the prevalent sound recording apparatus was the wax disk cutter. As a consequence of the lack of materials in the war-time economy, some inventive sound hunters made their own experiments with new materials within their reach. The name of the inventor who first utilized discarded medical X-ray film as the base material for new record discs is unknown; however, the method became so widespread in Hungary that not only amateurs, but the Hungarian Radio made sound recordings on such recycled X-ray films.

Owing to the lack of recordings of Western music available in the USSR, people had to rely on records coming through Eastern Europe, where controls on records were less strict, or on the tiny influx of records from beyond the iron curtain. Such restrictions meant the number of recordings would remain small and precious. But enterprising young people with technical skills learned to duplicate records with a converted phonograph that would “press” a record using a very unusual material for the purpose; discarded X-ray plates. This material was both plentiful and cheap, and millions of duplications of Western and Soviet groups were made and distributed by an underground roentgenizdat, or X-ray press, which is akin to the samizdat that was the notorious tradition of self-publication among banned writers in the USSR. The records were all simply called “roentgenizdat,” or “X-ray pressed” records.

According to rock historian Troitsky, the one-sided X-ray disks costed about one to one and a half rubles each on the black market, and lasted only a few months, as opposed to around five rubles for a two-sided vinyl disk. By the late 1950s, the officials knew about the roentgenizdat, and made it illegal in 1958. Officials took action to break up the largest ring in 1959, sending the leaders to prison, beginning an orginization by the Komsomol of “music patrols” that later undertook to curtail illegal music activity all over the country.” (Attribution, József Hajdú)

The flexi disc (also known as a phonosheet or soundsheet) is a phonograph record made of a thin, flexible vinyl sheet with a molded-in spiral stylus groove, and is designed to be playable on a normal phonograph turntable. Flexible records were commercially introduced as the Eva-tone Soundsheet in 1960, but were previously available in the Soviet Union as “roentgenizdat,” “bones” or “ribs,” underground samizdat recordings on X-ray film.

At present, to a vintage collector, records of this type an era will retail from around $150 and up.